While there have always been debates about the function of Fredericksburg’s Auction Block, documentation from the 1840s-1860s shows that dozens of enslaved people were bought, sold, and hired from the corner where it originally stood.

The Auction Block, often referred to as the Slave Block, the Slave Auction Block, and the Block, was installed at the corner of William and Charles Streets in downtown Fredericksburg around 1843, when the adjacent hotel (variously known as “The Planter’s Hotel,” “The United States Hotel,” “Charter’s Hotel,” and “Sanford’s Hotel”) was built. While no definitive evidence has been recovered that specifies the exact function of the Block — some speculate it originated as a carriage step and the large hole visible at its center indicates it might have served as a sign post advertising auctions — many believe enslaved people stood on it during sales, as at other documented sites of sales throughout the United States. There were at least twenty documented sales of enslaved people that took place on this corner from 1847 to 1862, involving more than three hundred enslaved individuals overall.

Hiring also took place at this corner. Enslavers rented out enslaved workers to other people for a set amount of time, collecting payment in exchange for the use of enslaved labor. There is also at least one documented reference to the auction of land at this same site.

A notice in the Fredericksburg News from January 6, 1854 disturbingly reads, “Large Sale of Slaves. Fredericksburg seems to be the best place to sell slaves in the State. On Tuesday, at Charter’s Hotel, forty-three slaves were sold for $26,000. One bricklayer brought $1,495. One woman and child, 5 or 6 years old, brought $1,350. Several were quite old servants. It was considered a tremendous sale.” This notice shows the amount of money exchanged for enslaved people, who “brought” (were sold for) the equivalent of thousands of dollars in today’s terms.

A formerly enslaved woman named Fannie Brown recalled witnessing a sale of enslaved people in Fredericksburg in 1860, possibly at the corner where the Block stood:

“I recollec’ one day I… went up close among de white folks gathered roun’ de warehouse peepin’ in through de windows to see de slaves. Den after a big crowd come roun’, I heard a n—– trader say, “Bruen…let my n—— out….” Jim, a big six-foot, tall slave, come out smilin’, and his shirt was took off, and den dey start exzaminin’ him. Dey jerked his mouth open an’ look at his teeth an’ den slapped him on his back, an’ den dey said, “Dis is a prime n—–. Look at dose teeth.” Somebody say one hundred dollars, another two hundred an’ so on ’till one thousand dollars was reached. Den Jim …. was handcuffed an’ put in de coffle wid de other slaves dat had been sol’.

While this corner seems to have functioned as the site most often used for the sale and hire of enslaved people, many other areas in the city of Fredericksburg also witnessed these violent transactions, likely including the corner of Caroline and Hanover Streets and the corner of Charlotte and Caroline Streets. It is important to note that the sale of enslaved individuals also occurred regularly in private transactions throughout the city of Fredericksburg, and that enslaved people were transported on slave ships that landed at the City Docks prior to the close of the International Slave Trade in 1808. Following that year, enslaved people were regularly forced to travel via “slave coffles” and ships headed further South. Enslaved people were held in private residences throughout the city and were also imprisoned in “slave pens” or “slave jails” at several locations owned and operated by slave traders.

According to historian John Hennessy, after the Civil War, the first documented reference to the function of the Auction Block came from a veteran visiting the city of Fredericksburg in 1893. Debates over the function and future of the Block occurred in the 1920s, when the local Chamber of Commerce requested its removal as a symbol of sectionalism (while confusingly arguing that enslaved people had never actually been sold from the Block at all). The community of Fredericksburg became divided over its purpose, but testimonials from several formerly enslaved people sold from the corner (validated by white men) and newspaper ads produced by local residents seemed to confirm its association with sales of enslaved people. The 1920 debates laid the groundwork for similar community conversations that would occur almost 100 years later.

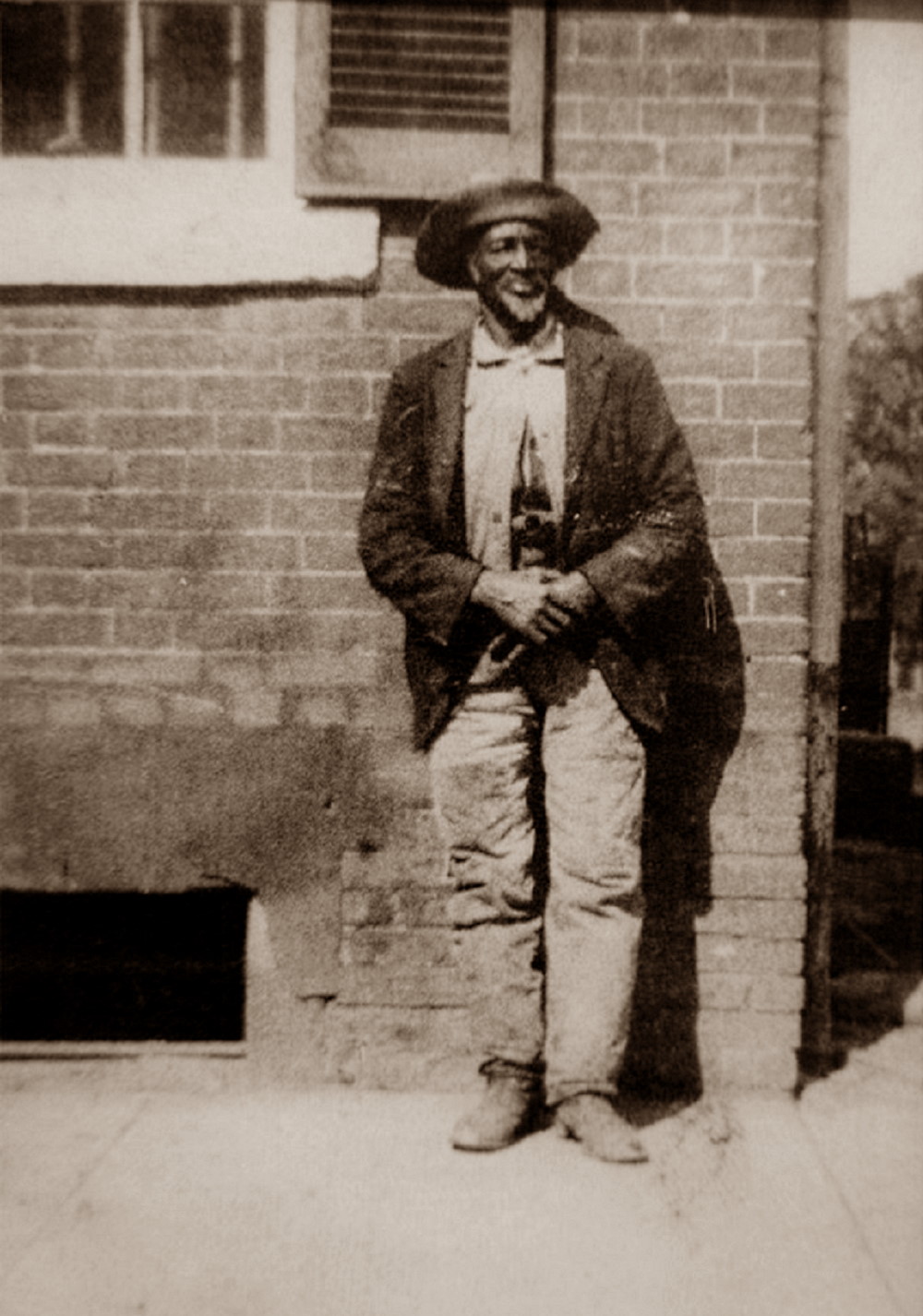

George Triplett

There are no known images of enslaved people on or near the Block prior to the Civil War. This image shows George Triplett, who is believed to be the last enslaved person sold from this corner in 1862. According to a note on the back of this image, George Washington Triplett was born in Stafford County on December 27th, 1833. After emancipation, Triplett lived with his family in Spotsylvania County and worked as a drayman, or wagon driver. The photographer is unknown, but this image was taken in September 1903. Image from the Brent Collection, courtesy of Lou Brent.

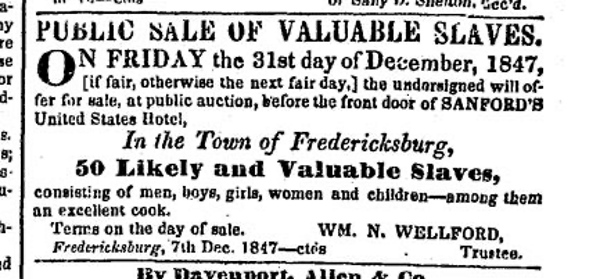

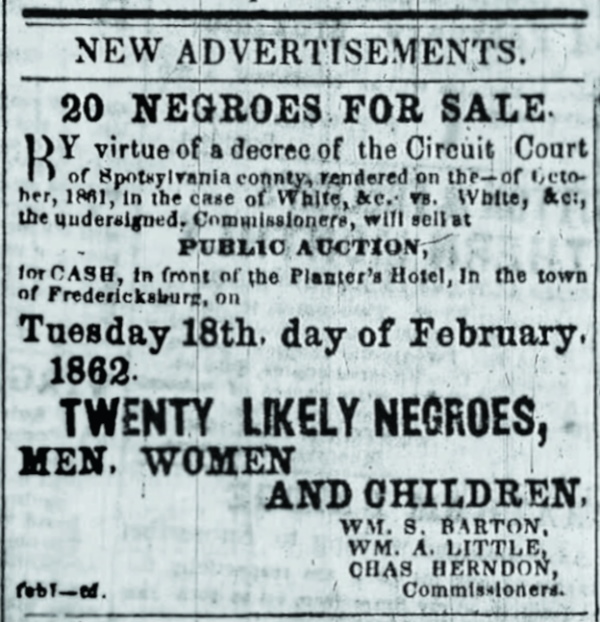

Fredericksburg News, February 1, 1862

This image shows an advertisement for the sale of enslaved people in front of the Planter’s Hotel, scheduled for February 2, 1862 (Fredericksburg News, February 1, 1862).