The “slave market” and the “slave trade” had immense financial impact across the United States, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the town of Fredericksburg. Enslaved people were often transported on slave ships until the close of the International Slave Trade in 1808; Virginia then became the largest exporter of enslaved people, with traders gathering groups of enslaved people and transporting them to be sold in urban centers in cities like Charleston, South Carolina, New Orleans, Louisiana, Atlanta, Georgia, and across the South. Between 1790 and 1860, more than one million enslaved men, women, and children were sold from states in the Upper South, especially Virginia, to the Lower South.

While buyers and sellers treated enslaved people like property, enslaved people understood the violence of these transactions and were vocal in their protestations. Charles Crawley, interviewed in Petersburg, Virginia on February 20, 1937, recalled: “There was a auction block I saw right here in Petersburg, on the corner of Sycamore Street and Bank Street. Slaves were auctioned off to the highest bidder. Lord! Lord! I done seen them younguns fought and kick like crazy folks. Child, it was pitiful to see them.” *

Delia Garlic, born in Virginia and interviewed at her home in Montgomery, Alabama on June 9, 1937, shared this haunting description: “Babies was snatched from their mothers’ breast and sold to speculators. Chilluns was separated from sisters and brothers and never saw each other again. ‘Course they cry! You think they not cry when they was sold like cattle? I could tell you about it all day, but even then you couldn’t guess the awfulness of it.”*

While oppressive laws, physical brutality, and institutional complicity at every level of government supported and sustained this violent system, enslaved people attempted to protect themselves and their families however they were able. Some appealed to potential buyers to purchase their families, or at least mothers and children, together. Some gathered information about potential buyers from other enslaved people and presented themselves favorably to buyers they thought might be less cruel, and unfavorably to those they distrusted. John Parker, in the autobiography His Promised Land, writes, “I made up my mind I was going to select my owner so when anyone came to inspect me I did not like, answered all questions with a ‘yes’ and made myself disagreeable.”

Finally, some enslaved people feigned illness or injury to avoid being sold. While not always successful, this tactic worked for some. Bethany Veney, in her 1889 narrative, described her experience: “I had been told by an old negro woman certain tricks that I could resort to, when placed upon the stand, that would be likely to hinder my sale; and when the doctor, who was employed to examine the slaves on such occasions, told me to let him see my tongue, he found it coated and feverish, and, turning from me with a shiver of disgust, said he was obliged to admit that at that moment I was in a very bilious condition. One after another of the crowd felt of my limbs, asked me all manner of questions, to which I replied in the ugliest manner I dared; and when the auctioneer raised his hammer, and cried, “How much do I hear for this woman?” the bids were so low I was ordered down from the stand.”

It is important to note that it was very difficult, and in many cases impossible, for enslaved people to advocate for themselves in a market which treated them as objects. However, it is also essential to understand the ways enslaved people recognized the cruelty of the system and created agency for themselves when they could.

Delia Garlic, Age 100

Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress

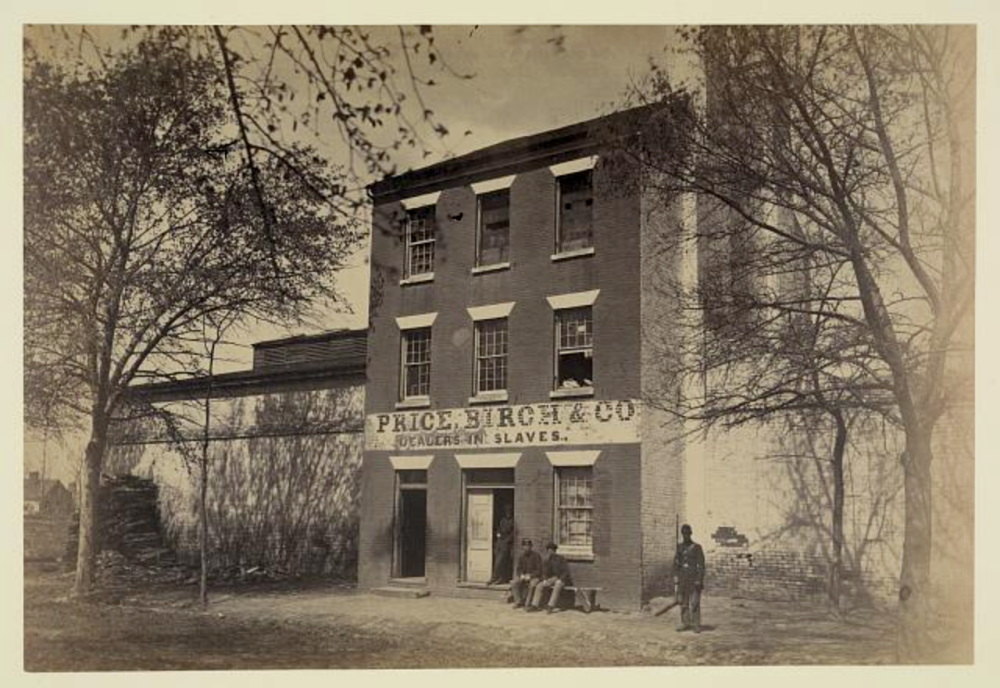

Slave Pen in Alexandria, Virginia

This image, courtesy of the Library of Congress, shows Union soldiers standing on Duke Street in Alexandria, Virginia in 1862. The text on the building behind them reads, “Price, Birch & Co., Dealers in Slaves,” showing the public prominence and lack of shame associated with the sale of human beings at this time. The photographer is unknown.

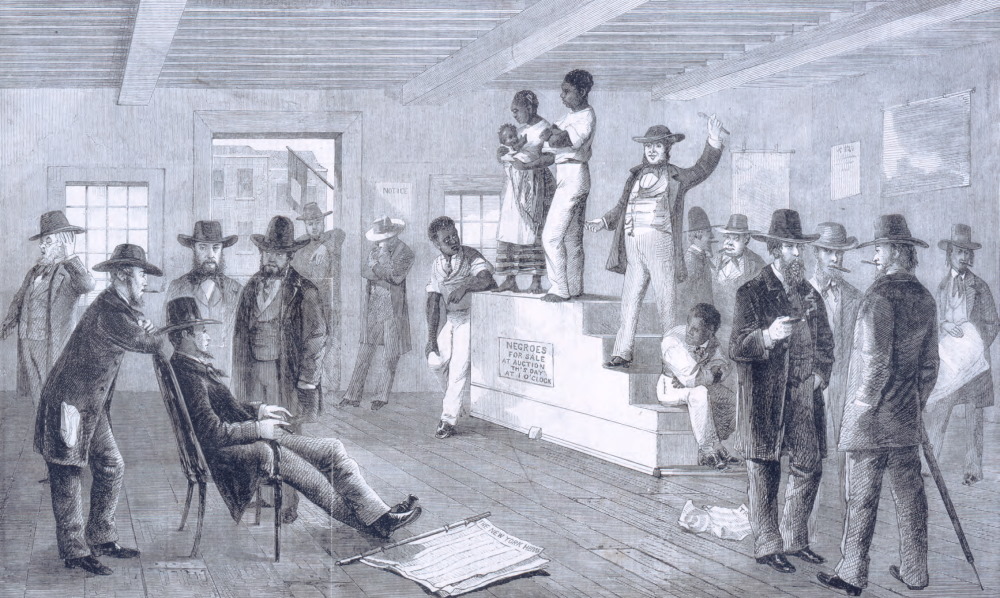

A Slave Auction in Virginia

This drawing, created in 1861 by George Henry Andrews, shows an enslaved family standing on an Auction Block in Richmond, Virginia. Enslaved people were often forced to stand elevated during sales and auctions so that potential buyers could inspect them. While surrounded by indifferent white men, humanity, fear, and tenderness for one another emanate from the enslaved man, woman, and child at the center.

*These anecdotes were recorded as part of the WPA slave narratives, a collection of histories by formerly enslaved people undertaken by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration from 1936 to 1938, part of FDR’s New Deal. The interviews have significant limitations, including the power imbalances between the mostly white interviewers and the mostly poor, Black interviewees, the length of time between the end of slavery and the time of the interviews, and the fact that many interviewers chose to record the interviews using stereotypical Black dialect. However, many scholars conclude that these narratives remain essential to accessing information about the daily life and experiences of enslaved individuals.